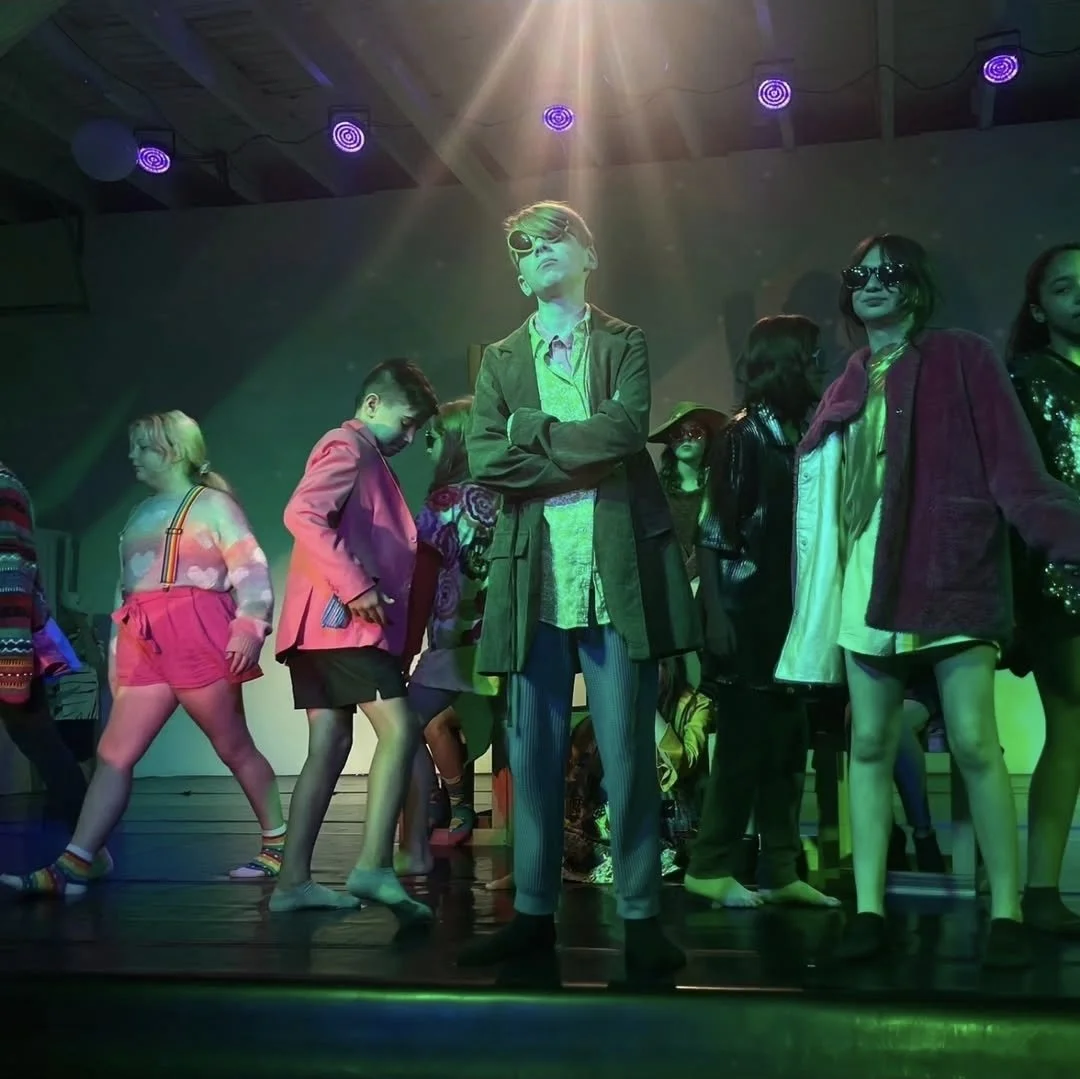

Simulating audience

Students engage in performance simulation at Philly PACK, 2026.

Simulating Performance: establishing trust in rehearsal, aka “The Container”

In the rehearsal classroom, educational theatre-makers are simulating performance—some students are engaged in the scene work, while others are acting as witnesses from the audience. As I’ve previously discussed, this witnessing is derived from Mary Overlie’s Six Viewpoints, and it’s an important part in the development of the scene because the witnesses help confirm that the piece is working.

There’s another important lesson in simulating performance: the witnesses are creating a safe, supportive container for the actors to engage in risk-taking and experimenting. It’s a way for the ensemble to work as a team, show each other care and compassion, and offer each other respect. The container is the magic sweet spot where empathy-training occurs.

Theatre is not only about learning to successfully communicate, but it’s also about gifting each other with respect. This gift is sacred, important and rare in so many parts of daily life. In the theatre classroom, freely offering respect to one another is a way of showing love and friendship. This is a powerful practice that establishes trust between artists, solidifies life-long friendships, and bleeds out into the rest of the artist’s everyday life. Knowing that you’re a trusted storyteller leads to confident, happy, artistic futures.

But how to we get young people to respectfully engage in performance simulation when there’s so much to distract them?

No phones. This is a no-brainer, but I often need to remind students of this one. Once, a student snuck a phone into my rehearsal and filmed two students engaged in a romantic scene. Then he showed the video at school to peers outside of the rehearsal classroom. This was a blatant breech of trust, and ultimately I had to involve parents. The student was remorseful—he apologized to those he filmed, and all three students went on to participate in what was ultimately a very successful project.

Chat Cafe: I’ve started designating a separate classroom for students who want to chat. In my experience thus far, I’ve discovered students actually want to be in the rehearsal room witnessing the work. Having an option and reminding them that they are engaging in a choice to stay and respectfully watch from the audience is effective in reigning in side conversations.

Opportunity to offer feedback. If the students witnessing the work are presented with the opportunity to offer constructive feedback, it gives them a sense of contribution and purpose. I like to prompt students by asking, “What did you see that was effective?” or “what did you see that was unclear?”

Faculty models The Container. I ask all faculty in the rehearsal room to model the locked-in respect that is expected from the students. As I always tell my team, sometimes our job is just watching. This models professional rehearsal etiquette.

When the rehearsal classroom is fully engaged in a respectful performance simulation, the practice allows us to make vulnerable, intimate work in a short amount of time. The payoffs are beautiful projects that inspire audiences and ensemble, as well as life-long relationships built on trust.

The VALUE of Practicum

Teen students in rehearsal at Philly PACK, 2024.

Curriculum as a Practicum: gaining experience beyond the classroom

Training young theatre-makers starts in the classroom that doubles as a rehearsal room. Applying theory in a real-world rehearsal is the best way to gain experience and growth for future actors, directors, choreographers, stage managers and designers. Students need a space to practice their technique, and the best place for this is the rehearsal room where we can simulate performance. When students have the opportunity to apply their technique towards an end-goal (performance), the curriculum is further connected to tangible experience. Well-trained artists trusted with real-world applications of the curriculum—practicum—will carry the technique and practices with them into future auditions, rehearsals and job interviews because they feel confident and successful in their tried-and-true skills.

The Eight Tenets of PACK

Principles / techniques that make up the performance education practicum at Philly PACK:

1. Ensemble (teamwork!) — Above all, theatre is a team-building art form. We work together to progress the storytelling. We are a community that serves and looks out for every individual member. The stronger our parts are, the stronger our shows are. We treat each other with respect, love and empathy. We value the strengths of every player, designer, crew member, and we value the audience for their partnership in the storytelling exchange of energy.

2. Vocalization (project!) — One of our central focuses in storytelling is vocal projection. If the audience cannot hear what we’re saying, the story halts. We must breathe deep and squeeze our stomach muscles to get full sound out. We value quality vocal projection that sounds comfortable to audience (screaming is painful for the actor and audience’s experience). We vocally warm up before performance, we value diction and annunciation, and we value vocal choices like regional accents for characterization.

3. Physical Choices — Another central focus in storytelling is complete embodiment of character with use of physical personhood. Character extends through toes and fingertips, top of head, heart/chest, shoulders, chin, neck and levels (knees). How does this character stand? Walk? Run? Dance? How does this character take up space? Every gesture and position of physical being should be intentional and informed from character.

4. Facial Expressions — One of the best communication tools we have for stage (and life!) is facial expression. The face tells the audience so much about the characters’ moods. We use expression of the eyes and eyebrows, mouth, and the tilt of chin to say how our character is feeling. Sleepy, sad, mad, frustrated, scared, annoyed, happy, excited, anxious, surprised, alert, confused, and any feeling humans can feel!

5. Script Analysis — Context: what time is the play set in? What time was the play written? Who wrote the play? Why did they write it? Who is my character? Why do they say this line? How do they say it? Who are they talking to? How does the character feel about this scene/scene partner? Also: we value toting script home and back to rehearsal every time, and we value memorization of lines and lyrics and blocking in a timely manner to allow optimal rehearsal time for off book character development.

6. Character Development — Each actor combines vocalization, physical choices, facial expressions, and script analysis to develop their characters in full. We value homework! Thought must be applied at home, so that actors/performers can bring ideas into the rehearsal process: we value trying choices out in rehearsal. Be brave, make BIG choices, and trust yourself and your team. We work together to create dynamics between characters that help the progression of the story.

7. Respectful of Design — If it’s not your prop, don’t touch it. We respect and love each part of the design. We know that love and thought went into each design: props, costume pieces, backdrop, set pieces, programs, lighting, sound design, house design, etc. We treat designs with care and we treat designers with respect because THEY WORK HARD for the good of the show. We know that if a prop, costume piece or any component of the design gets broken or lost, someone has to re-make it or fix it.

8. Lock the Blocks! This is a metaphor for safety at all times. Our top priority at PACK is safety. We look out for each other, we lock the rehearsal cubes (blocks), and we are aware of personal space and boundaries in the rehearsal/production process. PACK students must always conduct themselves in a safe manner that protects themselves and each other. We love each other and we want to keep every one safe.

Adapting for education

Students rehearse for Jess Noel’s adaptation of Misty of Chincoteague (PACK, 2022). Puppets by Kat Caro.

Adapting for Education: writing scripts for the classroom

Adapting for the theatre classroom is a muscle I love to work. It might be my favorite part of my job. While I enjoy being in the rehearsal room and creating with my students, I absolutely adore sitting at my desk and imagining stories that are perfect fits for them. I dream up dialog, and I can see each scene in my mind before we even start the rehearsal process. It’s such a pleasure to know who I’m writing for, and why, and often the ideas for my adaptations come like lightening strikes. BOOM! Suddenly I’m obsessed with a story, and there’s no stopping me from adapting it into a script.

Sure, it would be easier to order a packaged musical from MTI or Concord Theatricals. These are usually crowd-pleasers that everyone enjoys and can sing along to. But finding interesting, compelling things for a hundred students to do in a pre-packaged “Broadway Jr” or “School-version” show is almost impossible. I know many directors are able to scrape up parts for a huge student ensemble. But for me, I’d rather write my own adaptations for my students because it guarantees that each company member will have something important to say and do. I want every single one of my students, not just the lead players, to feel they are essential to the project. I’ve discovered the easiest way to ensure this is by writing my own scripts.

I enjoy taking an idea, concept, theme, or visual, and customizing it into a script for large groups of students. For example, adapting Marguerite Henry’s Misty of Chincoteague was born from a visual. During the summer of 2022, my IG feed was flooded with images of National Theatre’s production of War Horse where the company used life-size horse puppets manipulated by two or three ensemble puppeteers. The photos and video from this production were so inspiring, and I knew I wanted to attempt something like this with our young students. I’m lucky enough (so blessed) to work with production designer and brilliant puppet-maker, Kat Caro, who said she could absolutely build us a life-size horse. From this idea, the Misty of Chincoteague adaptation was born. I got to re-visit a classic from my childhood, and adapt the story into a dynamic script for my students, all with visuals in my imagination of a life-size horse puppet galloping across the stage. I had a lot of fun adapting Misty.

Sometimes, ideas for adaptations come from socio-political trends in current culture. I want to provide opportunities for my students to say important, relevant things with their art. Even though they are young, students are quite aware of headlines, policies, and important ideas, and they deserve the opportunity to meet the moment with purpose and intention. Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray is one such adaptation where the message of our project, as well as the central themes, align with today’s social media trends (obsession with youth and beauty) as well as politics (cultural attacks on lbgtqia+ communities). Students feel empowered through opportunities in their art-making to discuss hard, contemporary truths. It’s exciting to watch teens excavate social-reform messaging from my scripts, and I think this might actually be the whole point of why I write in the first place.

Coming up: I recently signed an exciting use contract with a very prominent American novelist. He’s one of my favorite writers, and this is such a dream come true! I’ve obtained exclusive permission to adapt two of his stories for PACK’s Spring 2026 educational projects, and I can’t wait to share more. The ideas behind these adaptations came from a few inspirations (1) powerful female lead characters who use their minds to enact change (2) revenge (3) my continued obsession with fabric and shadows. Stay tuned! I’m so excited to share who the writer is….can you guess?

Mary Overlie & “Hug School”

Teen students rehearse for Stardust, Philly PACK, 2025.

“Artists are invited to read and be educated by the lexicon of daily experience…working directly with these materials, artists learn performance’s essential language.” —Mary Overlie, Six Viewpoints.

My first experience with decoding and deciphering body dynamics came from NYU Professor Mary Overlie’s 2003-2004 Viewpoints workshop at Texas A&M University where I was a Performance Studies undergrad. She introduced me to the idea of an intellectual exchange and discussion between the performer and the witness or viewer. I use her concepts and theories in my classroom with young artists, especially when I’m assigning or blocking touch, and I’ve noticed the most student engagement occurs during our “touch dynamics” lessons. Today’s young artists are inspired and challenged by physical connection assignments.

Touch dynamics means deciphering the messaging between two or more actors engaged in physically touching each other. This could be a handshake, a hug, a fist bump, a stroke of the cheek, or any time actors touch each other on stage.

Artists use what they see in real life to inform authentic performance dynamics. Sometimes, however, it takes time to craft this authenticity. The audience is essential during the process of crafting authentic communication because they witness, watch and decipher the meaning of the moment. In my classroom, the students witnessing the work are expected to offer up what they see/what the work means to them. This classroom partnership is directly sited in Mary Overlie’s Six Viewpoints theory.

Mary Overlie, a post-modern theatre practitioner and educator, says truly authentic performance work requires two participants: the creator and the observer. The creators are making the physical and emotional choices for how to communicate a particular moment, while the observers are witnessing and decoding the story/emotion/moment.

Mary Overlie challenges performers to “read the lexicon of daily experience.” In other words, actors have the responsibility of noticing how humans interact and touch each other in real life, then they can bring the insights into their performance work by replicating what they’ve observed. The audience’s role is to hold the actors accountable for replicating an authentic dynamic. The audience asks, “Is it working?”

One of the most interesting uses of Overlie’s ideas is lovingly nick-named “Hug School” in my classroom. This curriculum is an exploration of authentically communicating two or more characters’ emotions through the use of touch, specifically hugs. When successful, actors hugging each other should not seem like effort. Rather, hugging should appear as natural as breathing. However, what teachers have seen in the post-pandemic theatre classroom is that touch between actors needs choreography and time to develop a necessary level of trust.

I’ve been a theatre teacher for twenty-six years, so I remember touch in the classroom before the pandemic. Back then, students of all ages were more receptive to experimenting with touch dynamics. For example, I could ask two actors to communicate a greeting between brothers who haven’t seen each other in ten years, and I would witness an exuberant embrace with charged energy at full speed towards each other. Chests crashed together, chins wrapped eagerly around each other’s shoulders, and necks would cradle together. Or, I might have asked for a hand-hold between characters who were just starting to realize they were in love. Pre-pandemic students could comfortably communicate curiosity as their fingers discovered how to lock together.

Students were much more prepared to engage in touch experimenting before 2020. But post-2020, more patience and creativity are essential in the process. Students are much more reserved with touching, and educators and parents know this is because social distancing became such an essential part of life for several years of young people’s social development. We continue to see the repercussions of this enacted distancing; it was important for children and teens to stay six feet apart. They were not encouraged to touch one another. But now, five years later, it’s challenging to help them push past what was once vital but is no longer serving performance training.

I offer opportunities for my students to explore touch in a safe and supportive container. First, there are hand sanitizing stations all over the classroom. This is a valuable first step because no matter where students came from—the bus, the subway, school, the dog park—they can feel prepped and ready to hold hands, touch elbows or shoulders, and even hug because their hands are clean. It’s a gesture of kindness towards their fellow scene partners. Hand-sanitizing seems like a no-brainer, but it’s worth mentioning because I’ve seen this practice make a huge difference in these assignments. Recently, I asked a group of nine actors to hold hands and make a paper-doll chain shape. There was hesitation until I quickly presented the hand sanitizer and gave everyone a squirt. This simple act signified permission to safely hold hands.

Next, we train our students to communicate with each other about consent. It’s become the norm in my classroom for students to ask each other if it’s ok to touch. I hear constant questioning like “is it ok if I touch your shoulder?” Eye contact has a lot to do with comfort. When asking another actor for their consent to engage in touch dynamics, it’s important to look each other in the eye and first connect through sight. Eye contact establishes trust. It’s vulnerable to look into someone’s eyes, and barriers are broken down with eye contact. Looking into someone’s eyes and connecting via sight is a first step in physical touching.

Another important element, as previously mentioned, is time. Usually, the comfort between actors who are engaging in touch requires several rehearsals. Students don’t often complete the task in the first go-around. Most of the time, a hug will appear awkward and strange until, suddenly, it looks natural and comfortable. This authenticity can take two or three rehearsals. But, once students feel confident and successful in authentically portraying hugs, hand-holds, handshakes, etc, doors are opened for discovery. The repetition goes a long way in breaking apart discomfort.

The dynamics of two actors engaging in touch is a wellspring of experimental curriculum. Two students on stage under the stage lights are portraying a storytelling moment, while the rest of the class/ensemble is watching from the audience. The students engaging in the touch on stage are discovering ways to authentically communicate the moment, and the students in the audience are able to catalog what choices are working, and what they might do differently if given the opportunity in the future to engage in the quest. As the teacher, I like to facilitate discussion about the dynamics of the connection with questions like, “what are you seeing? And what is working?” These prompts challenge the students in the audience to offer insight from their viewpoint as the witness, and the prompts add value to the audience’s participation.

For post-pandemic young people, “hug school” offers opportunities to push past discomfort and into discovery. These student practitioners are ultimately becoming master communicators in the art of physical expression, and I believe this will serve them in any field they choose to pursue later in life. There is a great need for emotional intelligence in the future of our species, and those who can harness and understand the physical dynamics behind emotional connection will lead the way into a more compassionate tomorrow.

Concept Theatre for education

Teen students at Philly PACK rehearse for Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Concept Theatre for Education: drawing connections to real life

Something interesting happened last night while I was in rehearsal with a group of twenty teen theatre students. It reminded me of the importance of context, concepts, and drawing parallels between the work and the world. In professional theatre-making, we call this study dramaturgy, and in the classroom, this is an opportunity for students to connect the dots between the historical work and the present-day politics, sociology, or movements. When the connection is made, and the light-bulb goes off for the students, it’s an educator’s reward.

My teens are currently in rehearsals for an adaptation I wrote of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Last night, we were blocking a scene when Basil (the painter) visits Dorian (the muse) to ask if he can borrow back the painting and exhibit it in Paris. Dorian panics because he does not want Basil to see how hideous and monstrous the painting has become, but Basil thinks Dorian does not want the painting exhibited because it will reveal how the painter is in love with his subject.

Basil (to Dorian)

And then, one day, the painting was complete. I stood back to view it, and I was struck with horror at the realization that…it gave me away. Everything I felt for you is there in the painting. For all to see. I knew I could never exhibit it because then the whole world would know, Dorian, that I…am…in love—

Dorian

Don’t say it, Basil.

Basil

But you must’ve seen it. In the painting. You must know that if anyone else views it, they will guess my secret.

After blocking the scene and running it a couple times, I asked the group what Basil means when he says “I was struck with horror at the realization that it gave me away”? Several hands went up. I called on a student who replied, “Because you couldn’t be gay in the 1890s. It was basically a death sentence.”

Bingo.

This led us into a discussion about the consequences of homosexuality, or even alleged homosexuality, during the time Oscar Wilde wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray. I mentioned the author himself was jailed for homosexuality allegations; Wilde was found guilty and served two years in prison. Some students were already aware of Oscar Wilde’s sentence, but many students were not. Our discussion shed light on the context of the play in 1890, but it also drew a parallel as to why the story is important today.

The Picture of Dorian Gray is relevant today for so many reasons, and that’s why it’s considered a classic. In the classroom, we’ve discussed themes of ownership, fan culture, and vanity. We’ve also discussed the dangers of wanting to look young forever. But the discussion last night about Oscar Wilde’s jail sentence for being gay hit hard.

We drew a connection: it is no secret that LBGTQIA+ people are under attack today.

Teens are online, reading the news and watching videos about anti-LBGTQIA+ agendas and policies coming down the pipe-line from the current administration. The rhetoric is affecting today’s young people, and educational opportunities to respond feel important to them. Teens need to be trusted to make art about politics.

Our dramaturgical discussion of the history of Oscar Wilde empowered my students in a new way: their mission became even more clear, and the responsibility to care for the work became an act of resistance.

There’s no reason to shy away from hard truths right now, and there is no point in sheltering teens—they already see and hear everything that’s happening in America and the world. I consider it my responsibility as an educator to provide them with opportunities to express their own feelings of frustration toward injustices they see online and in the real world.

Is online the real world? What’s real? The theatre classroom certainly feels like we’re engaging in something real. I’m thankful for rehearsals. As a teacher, my purpose has never felt more clear than right now.

Annie-B Parson & rule-Breaking

dancers in Of A Feather (Philly PACK, 2021) celebrate differences and similarities. Photo by Kat Caro.

Annie-B Parson and Permission To Break the Rules in dance…and in life.

“When an artist breaks apart familiar structures and reinvents them, there is disruption, and most of the gatekeepers and audiences are disturbed by this, but the audiences and the gatekeepers are unaware of what exactly is bothering them, and they just want the artist who is disrupting them to go away. But a few audience people, they crave the re-invention of structure, and these audiences are called ‘adventurous.’ I think they have just spent more time in the woods.”

—Annie-B Parson, The Choreography of Everyday Life, 2022.

One of my first really adventurous dance-theatre experiences happened in July, 2015 when I attended Big Dance Theater’s Alan Smithee Directed This Play: Triple Feature at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Becket, MA. From the audience, I sat and absorbed choreographer Annie-B Parson’s rule-breaking, and I remember feeling authentically inspired and empowered to make honest, artist-centered dance-theatre with my students.

At 33 years old, I was just starting to feel the effects of life-long ballet training. Decades of forced turn-out and pointed toes were only beginning to take its toll on my body. My knees, hips, ankles and feet were starting to ache, not to mention loudly crack. My orchestral bones sounded like a lightning storm all the time.

Watching Annie-B Parson’s choreography awaked something spiritual and truthful in me. Her dance company consisted of strong, healthy, beautiful dancers, but they were older than any professional dancers I’d seen in a performance. I always thought dancers had to retire at twenty-five years old because their bodies couldn’t handle the stress, but here I was watching Liz Dement, in her forties, dancing powerfully and purposefully. She moved like a great warrior-giant, and her artistry was unmatched. I had not seen this level of expression before on any other dancer.

Annie-B Parson’s choreography consisted of pedestrian gestures and traffic patterns one would see in every day life. She used music, text and sound to underscore sequences of movement that reflected the ordinary. This was my first time witnessing dance-as-theatre, and it was like looking in a mirror. I saw myself in each motion, and I walked away from the performance knowing I wanted to challenge the dance curriculum I had grown up studying: classical ballet.

Ballet is beautiful, and we love to revere it for it’s deep-rooted foothold in our culture. But ballet is violent on young bodies, it’s dangerous, and it’s highly disfiguring. You can look at any ballet dancer’s feet and know it’s true. This is why so many professional ballet dancers’ careers are over in their twenties. Most bodies can’t sustain the stress that ballet demands.

I do not offer classical ballet curriculum at my performance education center. Once I started feeling the effects of ballet on my joints and feet, I knew I could not in good conscience offer this training to young people. Instead, I offer a dance training curriculum that teaches safe jumping, turning, partnering and floor-work technique without any forced turnout or pointe. My goal is to train life-long dancers who feel confident in movement, and also feel healthy and joyful while dancing.

My curriculum focuses on meeting the dancer in their natural body-form, and empowering them with tools of artistic expression. Our focus is musicality, character development, expression AND technique. I also instill a strong appreciation for improvisation and shape-making using real-world movement; the dance of everyday life.

Annie-B Parson describes an experience she had while witnessing dance of everyday life in her book The Choreography of Everyday Life:

“When Donald Trump lost his job, there was large-scale spontaneous theater all across the country, a great fanfare, a raising of voices and dancing in the streets, and these dances were as natural as a leaf growing on a tree, and the trees were dancing too in reciprocity of the joy of the city. Long before Trisha Brown, before ballet, before disco dances and round dances and square dances, there was ecstatic dancing…we are still fundamentally the same, I thought. We are essentially a body in space with other bodies, expressing how we feel through our dances.”

Watching Annie-B Parson’s choreography informed how I choreograph in my classroom. I will always attempt to capture as she says, “essentially bodies in space, expressing how we feel through dance.”

Thank you, Annie-B, for your inspiration.

Pop Music in the class

Sadie Sink as Shelby in Kimberly Belflower’s John Proctor Is The Villian. Shelby dances to Lorde’s Green Light. Photo: A Shot magazine.

Above: students rehearse for James and The Giant Peach. Grasshopper lip-syncs to Giorgio by Daft Punk.

Pop Music in the performance classroom. It’s effective and inspiring! But is it legal?

As a dance-theatre teacher, I use pop music as a tool for character development and plot-sculpting, and I use my classroom as a music-appreciation platform to introduce students to genres of music and artists they might not otherwise be exposed to.

For the past twenty-six years, I’ve been customizing my own performance curriculum. The use of contemporary music in my classroom further engages young people in our projects, and when connections are drawn between the curriculum and popular songs, the students’ inspiration and motivation swell.

I was eighteen when I first started writing my own curriculum. Hired as a theatre education intern in 2000, I was responsible for teaching a Saturday morning Creative Dramatics class to k-2nd graders. I knew I wanted to produce Jack & The Beanstalk for family and friends at the end of our session, but the script needed to be something very specific; I needed enough parts for each student to have interesting directions to explore, simple and effective design, and really fun music we could sing and dance to.

I dug around in the scripts library, but I didn’t find what I was looking for. Sadly, the age-appropriate scripts were out-dated, and the music was boring. I couldn’t see myself fully-engaging my class of fifteen little artists with such stuffy material. I then realized I would need to write my own script. I would introduce students to fresh pop songs that fit within the context of the story, and I hoped the students’ families would love the final presentation of the project. I was right! The writing effort paid off, and the next semester’s enrollment tripled. After our presentation of Jack and The Beanstalk, I heard from so many parents who said their children were excited to come to rehearsal each week because “they loved the music and the dancing.” I had unexpectedly stumbled upon the secret formula: pop music in the classroom.

Today, I often reflect on the power of music in storytelling. Music has a way of reaching young people with an electricity and a magnetism that draws them into the content. Music breaks down barriers and meets students where they are. No matter what the day or the week has looked like, a great song can transport them into the exact moment in a story we’re rehearsing. Everything else from the rest of the world falls away. Music helps us get fully present in rehearsals.

When Stephanie Meyer was writing Twilight, she says she was listening to a lot of Radiohead. I ask my students to think about the relationship between music and writing. Did the songs’ melodic patterns dictate Meyer’s storytelling? Or did she already know where the story was heading, and she sought out music that fit the plot’s vibe? In other words, did Radiohead’s music help her flesh out the details of Bella and Edward’s romance? Or did their relationship lead her to Radiohead?

In the same vein, when playwright Kimberly Belflower first heard Green Light by Lorde, did she immediately think of The Crucible? When she listened to Lorde sing “those great whites, they have big teeth,” did she ponder about John Proctor, and conclude that he was actually the villain? Or did she know he was the villain, and she searched for a song Shelby could sink her teeth into in the final moments of the play?

Taylor Swift just dropped her twelfth studio album, The Life of a Showgirl. Naturally, this album with all its Shakespearean references, has me thinking of Hamlet and MacBeth, specifically Ophelia and The Weird Sisters. Taylor loves a drowning damsel in distress, and she also appreciates a prophetic-witch archetype. My imagination follows her into the mist and the lakes.

This puzzle-piecing of characters and stories is my favorite way to experience pop music. When I hear a song, I immediately assign a character or story moment to the song. The first time I heard Ed Sheeran’s song Photograph, I thought of The Boxcar Children by Gertrude Chandler Warner. Sheeran sings “we keep this love in a photograph,” and I imagined the four siblings, while navigating a trepidatious journey towards safety, carried with them a comforting photograph of their parents.

I wander down long corridors of storytelling, holding hands with every artist, album and pop song, until the lyrics have me hung up on plot points in classic stories I’ve known since I was a kid. I weave these idiosyncrasies into my performance curriculum, and the music appreciation lessons in my classroom have introduced hundreds of children/teens to artists they might not otherwise be familiar with. Students fall further in love with content when the sounds resonate with them. They leave rehearsal and listen to the songs at home, and this leads them down rabbit holes of discovering more new music.

But is this infringement?

I’ve heavily investigated “fair use” over the past two and a half decades, and I’ve interviewed several experts who all agree that using copyrighted music in educational classrooms is nuanced. Fair use permits educators to use contemporary music in their classrooms, and the unlocked motivation and inspiration have been helping teachers conjure magic since the 1970s. The most important consideration when establishing “fair use” in education is does this use effect the market value of the song? I rely on the safety of knowing with certainty that the use of pop songs in my classroom does not in any way effect the music market. This is primarily because I’m not producing a profitable show for public consumption. Our presentations are in my classroom, and these showings are for students’ family/friends.

A former student who is now a professional DJ once told me, “I learned about so many artists and genres of music from you.” Another student said, “the way you use pop music and contemporary references in the stories helps each project become so much more relatable, and the experience is unrepeatable.”

Working with pop music in the dance-theatre classroom is really exciting, and it keeps things alive and fresh for me. If I rehearsed the same show with the same music year after year, I would have burned out twenty years ago. The exploration of contemporary pop-songs for storytelling purposes continues to scratch at my curiosity, and it makes me smile. And pop music brings twinkles to my students’ eyes.

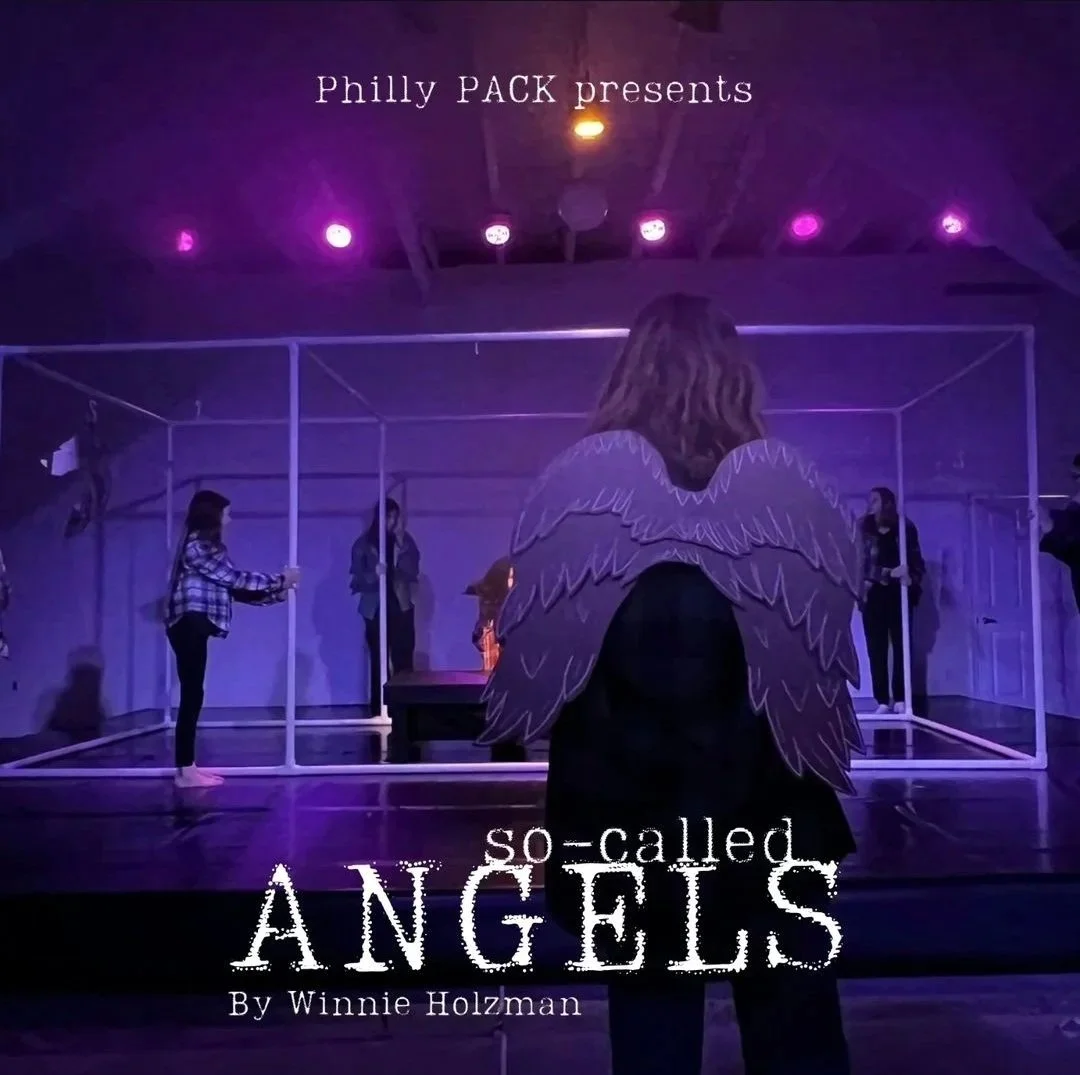

How to Be Present

Above: Teen students in rehearsals for Winnie Holzman’s My So-Called Life episode 15: So-Called Angels, 2023. This project was adapted/produced with special permission from Winnie Holzman.

How To Be Present

“There is only one interesting difference between the cinema and the theatre. The cinema flashes on to a screen images from the past. The theatre, on the other hand, always asserts itself in the present.” —Peter Brook, The Empty Space, 1968.

During 2020 lockdown, there was an undeniable hole in our culture. Something electric was missing. When a large group of people come together to focus, an intensity is created. The reaction is unmistakeable, and it’s important. It’s beautiful, and it’s vital! When the theatres were closed because of quarantine, that magic, intensity, and electricity were gone. Personally, I felt listless. Professionally, I felt adrift.

One could argue that we, as a culture, turned inward for a similar artistic experience that resembled attending a play: we stayed home and enjoyed films on our screens. Same thing, right? Storytelling, artistic expression, catharsis, comedic timing, relief, making sense of the present; all this can be found in movies. We are still getting the same thing from films, aren’t we?

As Peter Brook points out in the above quote from one of my favorite books The Empty Space, cinema is created in the past. Theatre is created in the past, but performed in the present. This will always be the defining feature that separates the two mediums, and my favorite reason why I love theatre. Engaging in theatre-making is one of the only things that makes me feel present. My brain stops wondering and worrying about the future or the past. I become simply still and here. In the Now. It’s glorious!

Peter Brook also says there is almost zero difference between actors and audience. They are all in the same space for the same reason: to experience a journey together in real time. The journey will reveal itself in different ways to different people because that’s the beauty of being diverse humans. But they are all in the room together with the same goal. The only difference between actor and audience is that actors prepare before the showing, and audiences do not. The audience comes into the space ready to receive the creation, and the actors come into the space having rehearsed the creation. But all participants are experiencing presence, nowness, and true being.

In the theatre, there are zero opportunities for editing. There are no takes. There is not one artist who goes back through the footage and strings together the best moments for the final interpretation of the story. In live performance, all participants are gathered for the search. They are searching for meaning, manifestation, ideas, emotions, clarity, and presence, whether audience or actor.

How to teach presence in the classroom:

Teaching this philosophy to young people today means establishing practices that draw them into the gorgeous NOW.

—In my classroom, the first thing we collectively do to signify a coming together and being present for the purpose of rehearsing is we take off our shoes. Feeling the stage floor beneath our toes has a grounding quality that brings the attention in to the current moment. There is also a peeling away of everything else that happened that day when one removes their shoes. It’s almost like saying “good morning!” or “welcome home!” when shoes come off. It’s a fresh start, no matter what else happened that day.

—We also leave our phones outside of rehearsal. Nothing takes a person out of scratching, discovering, and excavating meaning from the script or shapes like a buzz from a text or a social media notification ping.

—Another valuable practice in teaching presence is creating an optimal performance simulation. This means some of us watch from the audience and observe silence while other company members engage in scene work, choreography sessions, or vocalization/music sessions. If rehearsal is a simulation of the performance, we must observe silence during scenes that don’t involve us. In an ideal performance, we do not expect the audience to scroll on their phones or talk to each other during the show. Young students are capable of simulating performance and exhibiting high concentration, and this is good practice for the level of focus that will inevitably be needed to pull off the production.

—As we (young actors and faculty) prepare on our end for the performances, we are also preparing to be good audience members in future shows we attend. All of these simulation elements go a long way in creating curious, focused future theatre-goers.

—There are always opportunities for collaboration in a theatre classroom, but teaching collaboration to young artists means teaching respect, listening, and waiting your turn.

A fun lesson plan:

Once of my favorite things to do in my classroom is to take a story that has been told through film, and stage it. There is a clear curriculum through-line in this exercise that reveals further truth and insight when the story is rehearsed and performed in the present. It’s such an exciting way to show students the power and magic of the presence of theatre. Students have seen the filmed version in all its edited, final-cut glory, and now they get the opportunity to tell the story in real time, armed with their discoveries and fresh perspectives from rehearsal.

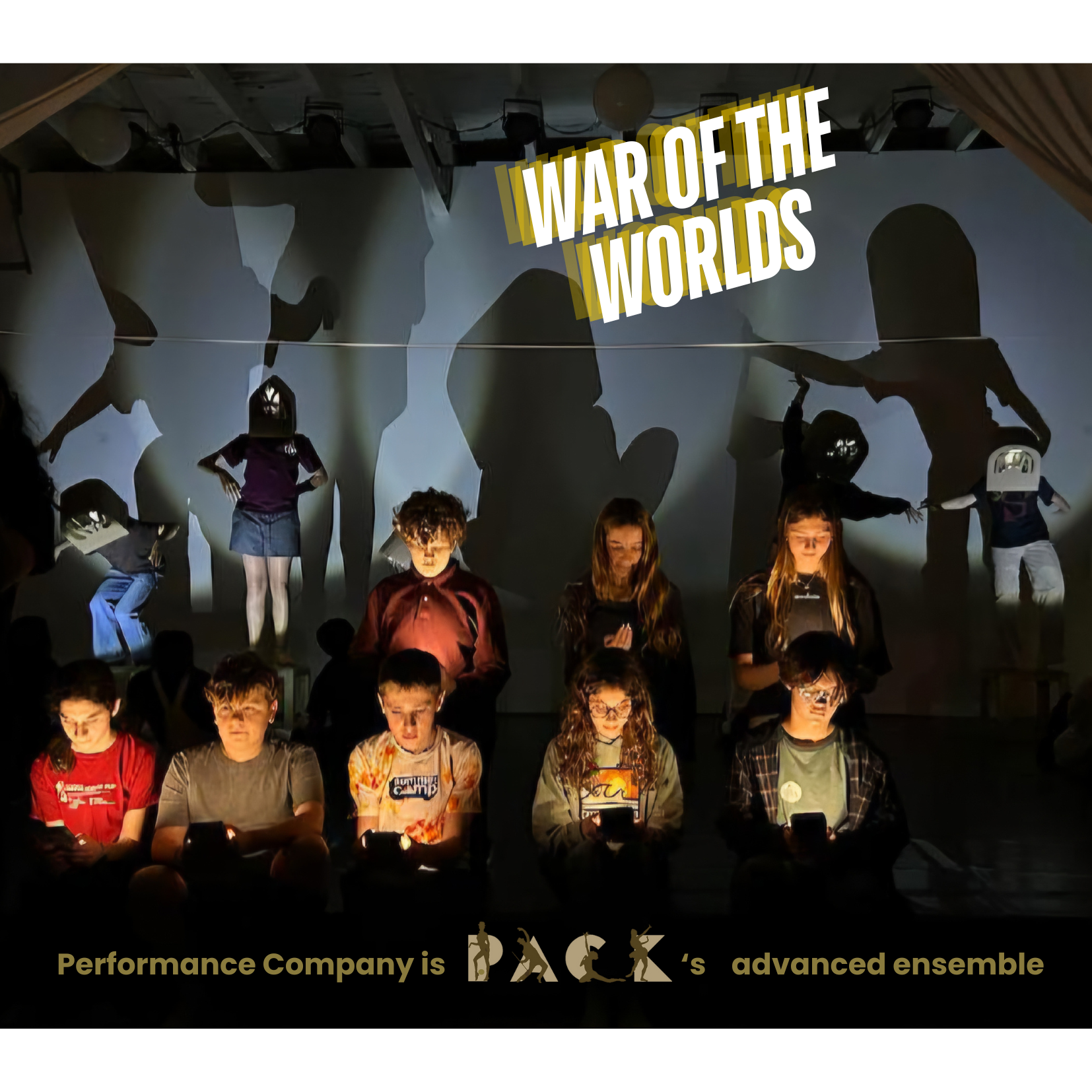

shadows & shapes

Shadows. Making shapes. Step one of teaching empathy.

Above: Teen students rehearse for Jess Noel’s adaptation of H.G. Well’s War of The Worlds, Philly PACK, 2024.

Shadows. Shapes. For me, the two words are almost interchangeable.

Have you ever noticed we dream in shadows? Or, at least, I do. Outlines are powerful. Our imaginations will fill in the details. Our brains don’t need to know the color of hair or eyes, or even t-shirt. All we require is a shape to provide every bit of information we need to decipher the dynamics of the moment. We can tell everything that’s going on simply by studying the outlines.

Shadow work is extremely rewarding, especially in the theatre. It’s like a puzzle, and if you can solve the challenge, you meet people in the delicious space of Understanding Each Other. This understanding is the purest goal of performance.

Shape-making is universal and transcends language barriers. You want the audience to guess what you’re trying to say, and the quest is to make it as easy on them as possible. In rehearsal, you chisel, and you shape-make. You’re on a mission to discover and project the most distilled version of the moment. You want to be understood, so you simplify the gesture and the body, and you ask the viewer “can you see me?”, but what you mean is “can you understand me?”

War is an interesting shadow-work concept. Make a shape with your body. Does it communicate violence, terror, loss, greed and sacrifice? Does your shadow tremble. Do you puff your chest to try and stop the quivering heartbeat?

Mother is another challenging shadow to experiment with. She is a large shape that expands and contracts with love, but also with concern and momentum. She moves forward while still preserving what’s left behind. She is protective and holds her love close, but she also lets it run free.

Change is inevitable in life, so change is important in shadow work. Children grow into young adults, adults shift into withered elders. The power in change lies in the consistency. Change will always occur. Therefore, a shadow denoting change should be a familiar series of two, maybe three projections. Two or three shifts in the body communicate change.

Why is shadow work important?

I believe the significance of shape is a long-forgotten communication tool.

Think about riding on a train. Your eyes scan the other passengers, and you can tell which are tired (they slump, their chins droop), which are anticipating something exciting (their heads are lifted, their shoulders are rolled back, their hearts are pointed up), and which are listening to a great song (heads bob and sway, eyes turned upwards, ears point up to the ceiling a bit).

If we all took the time to empathetically decipher one another’s physical communication, we would need less explaining, and there would inevitably be less misinterpretation that leads to frustration, or even sometimes ends in violence. We would need less words, and we would feel less confusion. There would be more seeing each other through a vocabulary of physical expression.

Shape-making and shadow-deciphering are education tools that teach empathy. What do you need to make a lesson plan? A white wall and a flashlight. Turn out the lights, flick on the torch, and GO! Teach children to investigate outlines, and suddenly we have a generation full of attuned detectives.

Jessica Noel teaches shadow work, physical dynamics, and shape-making as a part of her custom performance curriculum. For more information, email her at pennsportpack@gmail.com